INTRODUCTION

Facial palsy is a common problem from which many patients do not completely recover and hence have to live with chronic sequelae.1 These may include discomfort, functional deficiencies, and aesthetic defects that can have significant physical and mental consequences and a detrimental impact on quality of life.2,3

Botulinum neurotoxin type A (BoNTA) is a key tool in the management of facial palsy, reducing associated synkinesis and hyperkinesis while also improving facial balance and overall aesthetics.1,4-6 Improvements in quality of life have also been demonstrated.1,7 Furthermore, BoNTA injection is minimally invasive and repeatable, and usually associated with few major adverse events;1,4,6 hence, BoNTA may be used as part of a long-term management strategy.

Standardized protocols are currently lacking for the use of BoNTA in patients with facial palsy.3,7 Owing to the great variety of clinical presentations, every case should be assessed and treated on an individual basis. Nonetheless, it is important for practitioners to achieve some degree of systematization within their overall methodology.

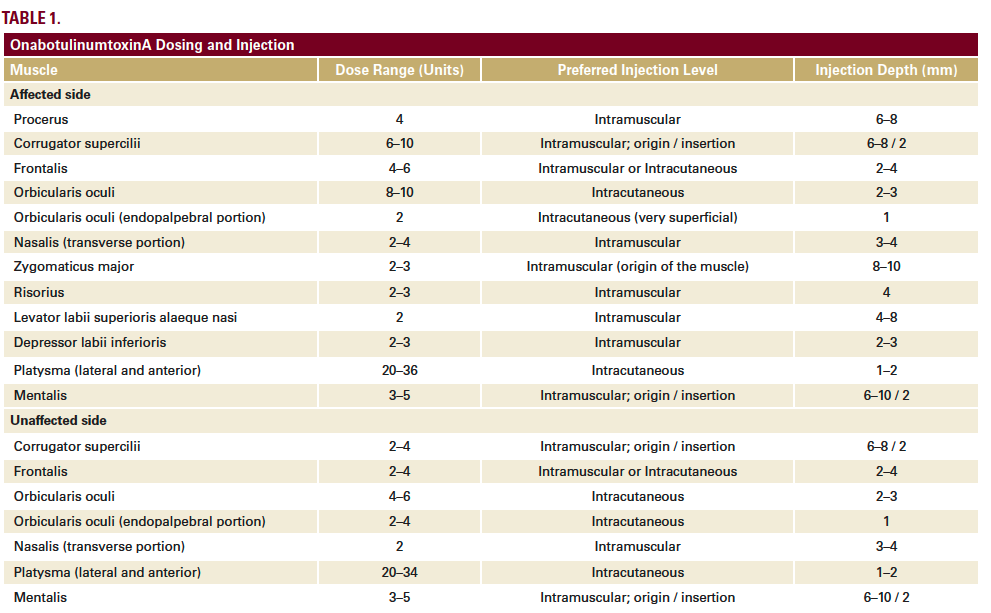

We have developed a full-face and neck approach to the treatment of facial palsy with BoNTA using standardized entry points, dose ranges and injection depths (Table 1). The overall focus is on:

• Treatment of both sides of the face to ameliorate synkinesis of the affected side, minimize hyperkinesis of the unaffected side, and improve overall facial symmetry.

• Treatment not just of the face but also both sides of the neck, with the aim of obtaining a progressive rejuvenation that minimizes the negative aesthetic effects of facial palsy.

Here, we present case studies of two patients with facial hemiparesis treated with BoNTA (onabotulinumtoxinA, Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) using this approach. The standard dilution was used for all treatments (50 units of onabotulinumtoxinA in 1.25 mL of saline solution).

CASE 1

A 53-year-old woman presented with left-side Bell’s palsy that had developed late in pregnancy when she was 40 years old. Routine blood testing and analyses for neurotropic viruses were negative. She was treated with corticosteroids until delivery.

Since then, she has had left facial hemispasm with painful tonic–clonic contractures, particularly in the lower face. Previous attempts at drug therapy with clonazepam, pregabalin, baclofen and gabapentin yielded only temporary and partial improvements. The addition of complementary treatments, such as B vitamins, physiotherapy, acupuncture and magnet therapy, had no benefit. She was also treated with BoNTA injections 2–3 times per year, primarily in the upper third with little treatment of the mid- and lower face; the neck was not injected. This approach was largely unsuccessful.

At 47 years of age, she underwent left retromastoid microcraniectomy to solve a vascular–nervous conflict at the origin of the left facial nerve in the bulb-pontin. After surgery, resolution of hemispasm was noted in the upper third of the face, with slight persistence in the middle third, but no change in the lower third. She was subsequently treated only with BoNTA on an irregular basis. The patient self-assessed the results using the 5-point Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS): 1 = worsened; 2 = no change; 3 = improved; 4 = much improved; 5 = very much improved. Using this scale, the change was rated as a 3, representing an ‘improved’ appearance.

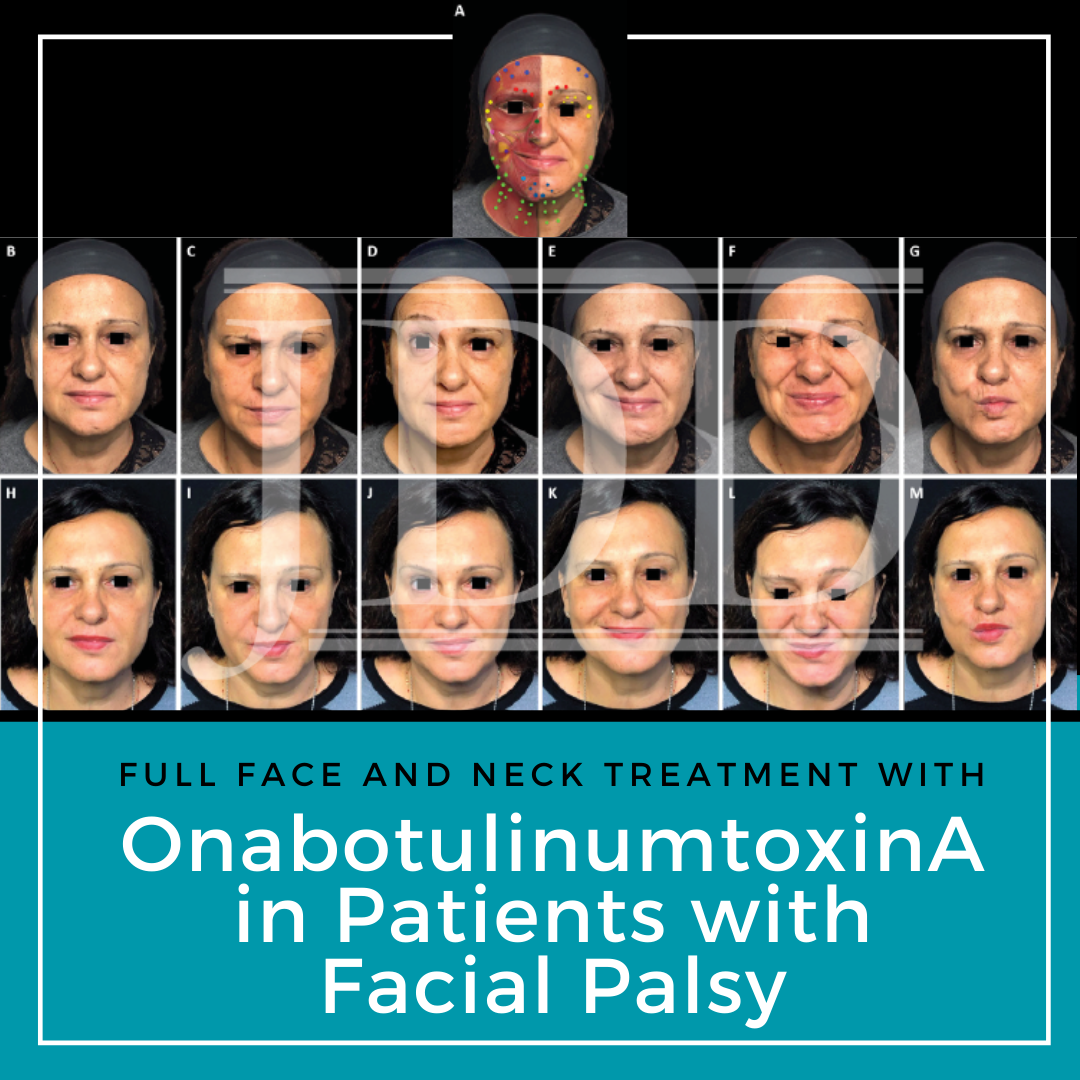

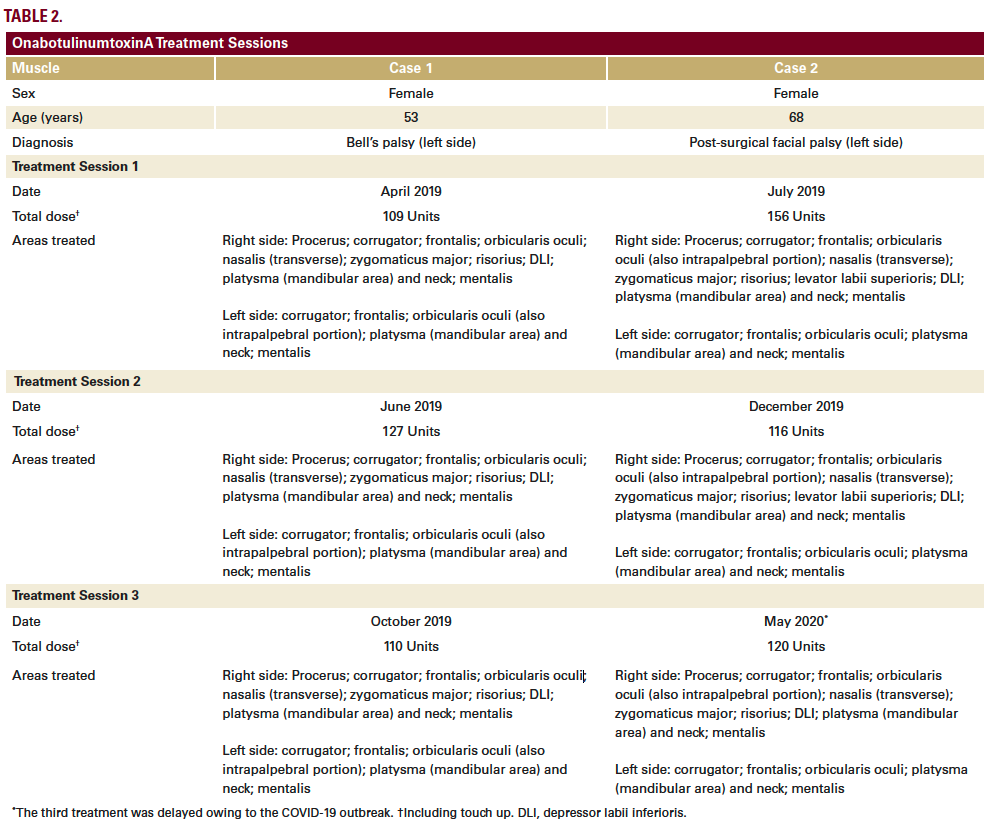

The patient began treatment at our center in April 2019, based on a full-face and neck approach using onabotulinumtoxinA (Table 2; Figure 1A). Repeat treatment using a similar injection pattern was undertaken in June 2019 and October 2019. Excellent results were achieved, as shown and described in Figure 1. Results on GAIS were assessed by the patient as a 5, representing a ‘very much improved’ appearance.

FIGURE 1. Full-face and neck treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA in a patient with facial palsy. A 53-year-old woman with left-side Bell’s palsy. Her injection plan with onabotulinumtoxinA is provided in (part A). She is also shown before (parts B–G) and 1 month after the first session of treatment (parts H–M). Notable features of the result include: good symmetrization, which was particularly evident in the eyebrows; relaxation of the chin area (which had been in constant contraction before treatment) and disappearance of synkinesis on the affected side; harmonization of the smile, with a reduction of hyperkinesis on the healthy side; maintenance of the ability to close her eyes despite treatment of the intrapalpebral portion of the orbicular muscle on the affected side; reduced platsymal contraction, which promoted a new aesthetic balance of facial contours; and general rejuvenation of the whole face, including the mandibular line. In part A: procerus, orange; corrugator supercilii, red; frontalis, mid-blue; orbicularis oculi, yellow; nasalis, dark green; zygomaticus major, pink; risorius, purple; depressor labii inferioris, pale blue; platysma, pale green; mentalis, dark blue.

CASE 2

A 68-year-old woman presented with post-surgical facial palsy on the left side, which had developed after excision of an acoustic nerve neurinoma at 45 years of age. For several months after surgery, she had to keep the eyelid on the paralyzed side closed with a plaster.

Passive physiotherapy yielded no improvement. After 6 months, she experienced spontaneous improvement and the eyelid resumed normal functionality.

At around 48–49 years of age, she began undergoing BoNTA treatment of the upper third of the healthy side of her face, with good aesthetic outcomes, self-assessed as a 4 (‘much improved’) on GAIS. Ten years later, she underwent a surgical neck lift with results that were initially positive but began to deteriorate within ~2 years.

The patient started treatment at our center in July 2019, based on a full-face and neck approach using onabotulinumtoxinA (Table 2; Figure 2A). Repeat treatment using a similar injection pattern was undertaken in December 2019 and May 2020. Excellent results were achieved (Figure 2), particularly considering her advanced age. The patient was especially satisfied with the improvements in the lower third, mouth, and neck areas. She assessed the overall results on GAIS as a 5, representing a ‘very much improved’ appearance.

FIGURE 2. Full-face and neck treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA in a patient with facial palsy. A 68-year-old woman post-surgical facial palsy on the left side. Her injection plan with onabotulinumtoxinA is provided in (part A). She is also shown before (parts B–F) and 1 month after the first session of treatment (parts G–K). Notable features of the result include: good symmetrization of the entire face; relaxation of the chin area and the eyebrow of the affected side (which had been in constant contraction before treatment) with associated disappearance of chin synkinesis and reduced upper eyelid synkinesis on the affected side; harmonization of the smile, with a reduction of hyperkinesis on the healthy side; maintenance of the ability to close her eyes despite treatment of the intrapalpebral portion of the orbicular muscle on the healthy side; and general rejuvenation of the whole face, including the mandibular line, chin and lips. In part A: procerus, orange; corrugator supercilii, red; frontalis, mid-blue; orbicularis oculi, yellow; nasalis, dark green; zygomaticus major, pink; risorius, purple; levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, cream; depressor labii inferioris, pale blue; platysma, pale green; mentalis, dark blue.

DISCUSSION

The approach employed in both patients involved injection of onabotulinumtoxinA into a wide variety of muscles on both sides of the face and neck. The total doses used (109–156 units per session) were substantially higher than in most previous facial palsy studies.4-6 This was because we did not limit ourselves to treating synkinesis, hyperkinesis and facial asymmetry, but also applied the principles of full-face aesthetic treatment8 to obtain an anti-aging, rejuvenating effect.

The two patients were treated differently according to individual functional alterations of the facial muscles, but the overall approach remained within our standardized framework (Table 1). In both cases, we have reported here on the treatment and outcomes across the first 3 sessions. These were given at intervals of 3–6 months, in line with the typical duration of effect of BoNTA, although there is evidence from previous studies of prolonged effects beyond 6 months in facial palsy.1 At each treatment session, patient photographs were captured in various projections both in static and dynamic pose. Results were verified at follow-up appointments 2–3 weeks after initial treatment. Touch-ups were given if necessary, typically to modulate the synkinesis that sometimes develops, particularly after treating the hyperactive (healthy) side of the face.

In both cases, patient photographs demonstrate the improvements achieved (Figures 1 and 2); GAIS assessments also suggested substantial aesthetic enhancements. Neither patient experienced any significant complications. This aligns with data from systematic reviews of previous studies of BoNTA in facial palsy, which have suggested low rates of major complications.1,6 Furthermore, a recent randomized trial comparing three different BoNTA formulations in patients with synkinesis observed no major adverse events.4Many facial muscles were treated that would not normally be included in aesthetic BoNTA procedures for non-palsy patients – such as zygomaticus major, risorius, levator labii superioris, depressor labii inferioris, and endopalpebral orbicularis oculi. Thus, a deep knowledge of the functional anatomy of the facial muscles is required. Furthermore, injection depth is crucial; some muscles must be treated at their deep origin, some at their cutaneous insertion, and others may potentially be treated at either (based on individual patient needs).Following initial BoNTA treatment, each subsequent round of therapy should be adapted as required. Indeed, injection quantities in the two patients described here varied somewhat between sessions (Table 2). We noted that some asymmetries reduced in severity between sessions. For example, the chin area was always hyperactive and synkinetic, but showed a high degree of improvement even as the pharmacologic effect of BoNTA declined over time. We also attained sustained symmetrization of the eyebrows. Our findings align with previous data suggesting that BoNTA continues to be effective over multiple treatment sessions in patients with facial palsy.9

Both patients were extensively treated in the platysma to achieve a lifting and anti-aging effect within the lower third of the face. Normally, to obtain a lifting effect during non-palsy aesthetic treatment, we would reduce the action of the platysma, which has a depressive activity in its mandibular insertion, thereby fostering the antigravity effects of the muscles of the middle third of the face. In palsy cases, one side of the face has no active elevator muscles. Hence, it is even more important to reduce platysma activity, in order to rebalance asymmetric tissue descent.

CONCLUSIONS

Use of BoNTA across the whole face and neck is a minimally invasive approach to the aesthetic treatment of facial palsy with a low risk of major complications and the potential for excellent results. When treating these patients, it is essential to find a balance between the relaxing effects of BoNTA and preservation of residual motor function. If treatment is performed gradually by a skilled practitioner, an acceptable compromise between aesthetics and function can be achieved.

In the two cases described here, we have demonstrated marked improvements in synkinesis, hyperkinesis and facial symmetry, and also shown an anti-aging effect similar to that achieved with normal full-face treatments using BoNTA.8Results stabilized across multiple sessions of repeat treatment.

DISCLOSURES

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

REFERENCES

2. Cabin JA, Massry GG, Azizzadeh B. Botulinum toxin in the management of facial paralysis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23:272-280.

3. Serrera-Figallo MA, Ruiz-de-León-Hernández G, Torres-Lagares D, et al. Use of botulinum toxin in orofacial clinical practice. Toxins. 2020;12:112.

4. Thomas AJ, Larson MO, Braden S, Cannon RB, Ward PD. Effect of 3 commercially available botulinum toxin neuromodulators on facial synkinesis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20:141-147.

5. Shinn JR, Nwabueze NN, Du L, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in botulinum therapy for patients with facial synkinesis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21:244-251.

6. Lapidus JB, Lu JC, Santosa KB, et al. Too much or too little? A systematic review of postparetic synkinesis treatment. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73:443-452.

7. Mehdizadeh OB, Diels J, White WM. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24:11-20.

8. D’Emilio R, Rosati G. Full-face treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA: Results from a single-center study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:809-816.

9. Neville C, Venables V, Aslet M, Nduka C, Kannan R. An objective assessment of botulinum toxin type A injection in the treatment of postfacial palsy synkinesis and hyperkinesis using the Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:1624-1628.

SOURCE

Content and images republished with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

The Journal of Drugs in Dermatology is available complimentary to US dermatologists, US dermatology residents, and US dermatology NP/PA. Create an account on JDDonline.com and access over 15 years of PubMed/MEDLINE archived content.

Did you enjoy this case report? You can find more here.