ODAC Dermatology Conference, in partnership with Next Steps in Derm, interviewed Dr. David Miller, Instructor in Dermatology and Medicine at Harvard Medical School and member of the Department of Dermatology and the Department of Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he is co-director of the Merkel cell carcinoma treatment program. Watch as he shares important updates on Immuno-Oncology (IO) strategies for melanoma.

Source: Next Steps in Dermatology

At the 17th Annual ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic, and Surgical Conference (ODAC) held January 17-20 in Orlando, FL, Dr. Desiree Ratner led a discussion on new and emerging therapies for advanced non-melanoma skin cancer discussion.

Treatment Options

The session covered several treatments for patients including patidegib gel 2% and 4% applied once or twice daily in patients with basal cell carcinoma. Patidegib is a topical hedgehog inhibitor made by PellePharm and its mechanism of action is to block Smo signaling, thereby inhibiting the hedgehog pathway that contributes to the development of basal cell carcinomas. This treatment has several advantages in that it does not contribute to hair loss, taste loss, or muscle cramps. It has the potential to treat and mitigate facial basal cell carcinomas in basal cell nevus patients. It is being studied in randomized clinical trials enrolling patients with Gorlin’s syndrome (basal cell nevus syndrome) in the United States and in Europe.

Hedgehog pathway inhibitor resistance is unusual but may occur as “rebound” tumor growth after drug cessation or secondarily after long-term smoothened inhibitor therapy. Resistance to hedgehog pathway inhibitors is classified into primary and secondary resistance. Primary resistance has been postulated to bypass mechanisms of genes downstream of smoothened, such as the G497 W mutation. Secondary resistance in patients who showed an initial response has actually been thought to be due to de novo mutations located on regions in smoothened to which hedgehog pathway inhibitors bind or selective clonal expansion of minority clones in the pre-treated tumor. Further studies are definitely needed to elucidate what drives resistance to hedgehog pathway inhibitors and how basal cell carcinoma resistance may be overcome by other novel, emerging therapies.

Patient Cases

Dr. Ratner presented a number of interesting patient cases with advanced basal cell carcinomas sometimes so large that patients lose mobility and function of a body part or organ. In most cases, locally advanced BCCs respond well to oral hedgehog inhibitors, which can be used for long-term control or neoadjuvantly prior to surgery. In the case of one patient, an aggressive orbital BCC caused contraction of the tissues around his eye, such that he was not able to open it. Despite treatment with an oral hedgehog inhibitor, his tumor continued to grow, resulting in destruction of his orbit and locoregional metastasis.

Samples of his tumor and normal skin were sent to Stanford University, which performed whole exome sequencing. In the studies of these samples, it became evident that the tumor should have responded to vismodegib but had developed resistance due to another as yet unknown mechanism. Therapies designed to override resistance such as second-generation smoothened inhibitors are under development.

Source: The Dermatologist

The following is an excerpt from The Dermatologist as coverage from ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical 2020 where Sailesh Konda, MD, and Vishal Patel, MD, reviewed the guidelines and discussed considerations for when and when not to perform MMS.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is considered the gold standard of treatment for many skin cancers. However, this option is not always appropriate for every situation and every patient. Several factors should be considered when determining which option to use, including tumor size, patient age, and aesthetic outcomes, for treating skin cancer.

The Dermatologist: What are the guidelines for determining what tumors should and should not be treated with MMS?

Dr Konda: The appropriate use criteria (AUC) for MMS was developed in 2012 by an ad hoc task force.2 In general, MMS may be considered as a treatment option for tumors on the head, neck, hands, feet, pretibial surface, ankles, and genitalia; aggressive tumors of any location; tumors greater than 2 cm on trunk or extremities; recurrent tumors, and tumors arising in patients with a history of immunosuppression, radiation, or genetic syndromes.

An AUC score is assigned to tumors based on their characteristics. Tumors with scores of 7 to 9 are appropriate, 4 to 6 are uncertain (in extenuating circumstances, MMS may be considered), and 1 to 3 are inappropriate.

However, practitioners should remember that these are only guidelines! Even if a tumor meets criteria for MMS, the physician and patient should still discuss all available treatment options—both surgical and nonsurgical— and take into consideration associated cure rates; long-term clinical and aesthetic outcome; the patient’s age and comorbidities; and risks, benefits, and adverse effects before deciding on a treatment.

The Dermatologist: What tumors often deemed appropriate for MMS might not actually require MMS, and why?

Dr Konda: Superficial basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in situ are tumors that have been deemed appropriate for MMS. However, these tumors may also be treated with topical therapy (imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil), local destruction, fusiform or disc excision, photodynamic therapy, and lasers (CO2 +/- diode for follicular extension). These treatment modalities may provide cure rates lower than but approaching those of MMS, and may be preferred by physicians and patients in certain circumstances. When discussing treatment options, patients should be made aware of any therapies that may be used off-label or are not FDA-approved.

Additionally, lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ) and lentigo maligna melanoma may be treated with either MMS (frozen sections), staged excision with central debulk and complete margin assessment (permanent sections), or wide local excision (permanent sections).

Source: Dermatology News

The following is an excerpt from Dermatology News Expert Analysis, Conference Coverage from ODAC.

ORLANDO – Dermatologists should be well versed in addressing common concerns that patients, family members, and the media have about photoprotection, Adam Friedman, MD, advised at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic, & Surgical Conference.

“Know the controversies. Be armed and ready when these patients come to your office with questions,” Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview at the meeting, where he presented on issues related to photoprotection.

Which SPF to choose and the impact of sunscreen on vitamin D are among the issues patients may be asking about. Sunscreen SPFs above 50 don’t technically provide a “meaningful” increase in ultraviolet protection, given that this value relates to filtering about 98% of UVB, but they still can provide some benefit, which has to do with real-world human error, Dr. Friedman said.

Source: Next Steps in Derm

Backed by a mountain of evidence, Dr. Zitelli walked us through the new and changing role of sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma in a riveting 20-minute talk presented at the 16th annual ODAC conference. Here are the highlights.

“Let’s separate what’s really evidence based from what you’ve been told.”

Before delving in, Dr. Zitelli skillfully laid the framework for his lecture. The crux of sentinel lymph node biopsy is based on the theory of orderly progression, in which malignant melanoma cells leave the tumor and preferentially enter the lymphatics and the first lymph node. This theory is rivaled by the anatomic pathway, in which malignant melanoma cells may enter the lymphatics or the blood stream, resulting in simultaneous dissemination.

Which theory is correct?

The overwhelming preponderance of evidence supports the latter anatomic theory – melanoma cells may enter the blood stream directly or the lymphatics, potentially bypassing the sentinel node. This anatomic theory is evidence based. It refutes the theory of orderly progression that the concept of sentinel lymph node biopsy is based on. Another common misconception is that lymph nodes are filters – they are not. Lymph nodes are sampling organs, sampling antigens in order to initiate an immune response.

With the groundwork laid, Dr. Zitelli went on to summarize the emerging evidence for sentinel lymph node biopsy. “This is what you need to know when you counsel a patient in order to obtain true informed consent.”

What you’ve been told: Sentinel lymph node biopsy improves survival

What the evidence shows: There is not a single solid tumor for which sentinel lymph node biopsy has been shown to provide a survival benefit.

We’ve been told that sentinel lymph node biopsy improves survival in intermediate thickness melanoma, because subclinical deposits are removed from the lymph nodes before they can grow. In fact, 33% of patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy, did so because they thought it would improve their survival. Yet, there is not a single solid tumor – melanoma, gastric, renal, thyroid or otherwise – where electively removing normal lymph nodes, even in the case of microscopic involvement, has shown a survival benefit.

A cornerstone trial, the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1), set out to prove the survival benefit of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. However, sentinel lymph node biopsy failed to improve melanoma specific survival. Subsequently, MSLT-2 looked at whether removing positive lymph nodes further down the line would improve survival in patients who had positive sentinel lymph nodes – this was also a negative study.

Source: Dermatology Times

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has classically been performed for regional disease control and to hopefully prevent disease metastasis; however, according to one expert, there has not been any good evidence to support this practice. As such, it is important for clinicians to focus on the evidence when planning the treatment and management of their advanced melanoma patients.

“Over the last decade or so, the role of SLNB has been changing, and there is no real consensus as to when to perform the procedure because it is a very rapidly changing field. The touted usefulness in survival benefit or prognosis of SLNB simply cannot be backed up by the available data, essentially rendering the appropriate use of SLNB in therapeutic limbo,” said John Zitelli, M.D., clinical associate professor, departments of dermatology & otolaryngology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn., who spoke at the Orlando Dermatology and Aesthetic Conference.

According to Dr. Zitelli, the theory that SLNB would provide a survival benefit was debunked with the MSLT-1 research study1 recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and the idea that the procedure was to be considered as the most accurate prognostic test was also shown to be untrue. There usually is no need to do a SLNB, Dr. Zitelli said. The Breslow thickness, as well as all of the presenting clinical pathological morphologic features, such as ulceration of the tumor, is a wealth of information that the clinician can use to contemplate appropriate further treatment and management of the patient. Many clinicians still prefer to perform SLNB, Dr. Zitelli said, reasoning that waiting until the tumor is palpable would likely be synonymous with greater complications.

“The premise is off, because if you’re performing SLNB on a lot of people and the complication rate is low but the number of patients who are getting the procedure is high, the long-term complication rate in a group of people who you manage with SLNB actually have more complications than the smaller group of patients who have a complete node dissection from palpable disease,” Dr. Zitelli said.

Controversy revolving around the role of SLNB and its true usefulness in melanoma therapy and management continues today. The current contemporary wisdom is that SLNB should be performed because the results could help determine which patients would be more amenable to adjuvant therapy.

Source: Next Steps in Derm

This information was presented by Dr. Jean Bolognia at the 16th Annual ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetics and Surgical Conference held January 18th-21st, 2019 in Orlando, FL. The highlights from her lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Daniel Yanes.

Despite being one of the more common reasons for consulting a dermatologist, the diagnosis and management of atypical nevi remain nuanced and can often be challenging. I had the opportunity to learn from Dr. Jean Bolognia on her approach to atypical nevi, and walked away with many pearls to share.

1. Identify the patient’s signature nevus and come up with a plan.

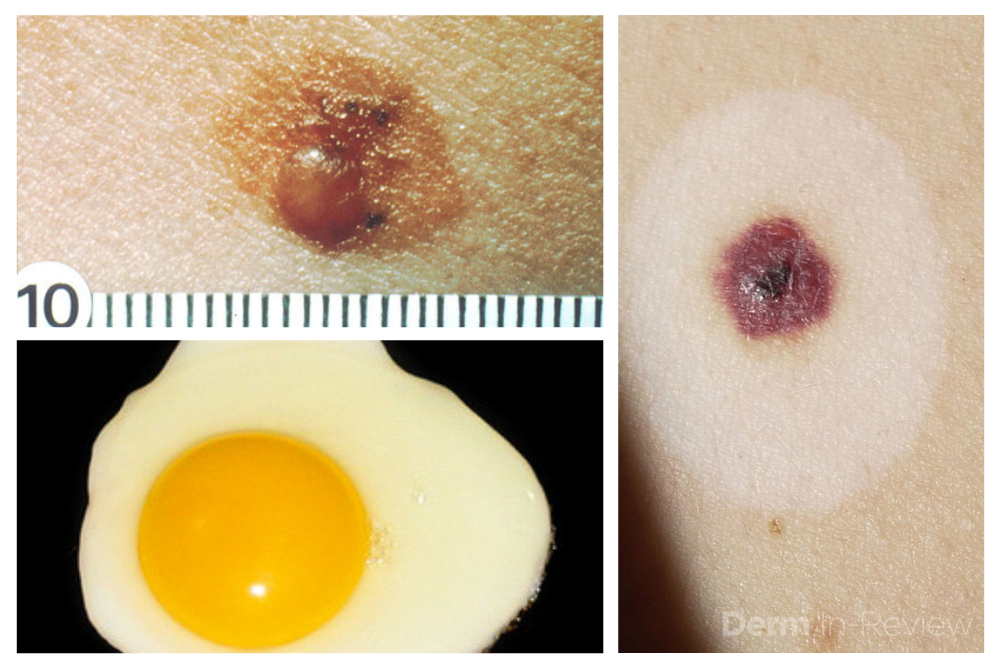

Sometimes it can be overwhelming to know where to begin when tasked with the patient who has numerous and atypical nevi. The first step is to identify the patient’s signature nevus. Do they tend to grow fried egg nevi, eclipse nevi, or cockade nevi? Are their signature moles all pink with little brown pigment, or are they pitch black with a wafer of scale? Identifying the signature nevus assists in determining the ugly duckling, and it will also help you develop a practical approach. In addition, if the patient has primarily pink nevi, palpation for induration versus soft flabbiness is helpful as banal intradermal melanocytic nevi can be pink in color. If the patient has primarily small flat black nevi, you should hone in on the presence of inflammation that is not simply due to acne or folliculitis. Creating an individualized plan is the key to a successful examination.

2. Nevi change, and sometimes it is simply an aging phenomenon.

In addition to identifying the signature nevus, it is also essential to understand how melanocytic nevi evolve over time. While nevi classically progress from junctional to compound and then to dermal, sometimes they simply fade away. In the case of fried egg nevi, the “yolk” becomes more raised and softer over time while the “white” of the egg gradually fades (figure 1). This results in multiple large dermal nevi on the trunk in an older patient. Patients can be taught that when a nevus elevates, determining if the lesion is firm versus soft can assist in distinguishing between the need for evaluation versus an aging phenomenon. Although not all changing nevi are concerning nevi, it is still essential to give the patient’s nevus of concern special attention, even if it doesn’t catch your eye at first.

Source: Next Steps in Derm

This information was presented by Dr. Jean Bolognia at the 16th Annual ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetics and Surgical Conference held January 18th-21st, 2019 in Orlando, FL. The highlights from her lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Daniel Yanes, one of the 5 residents selected to participate in the Sun Resident Career Mentorship Program (a program supported by an educational grant from Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.). Dr. Yanes was paired with Dr. Jean Bolognia as his mentor.

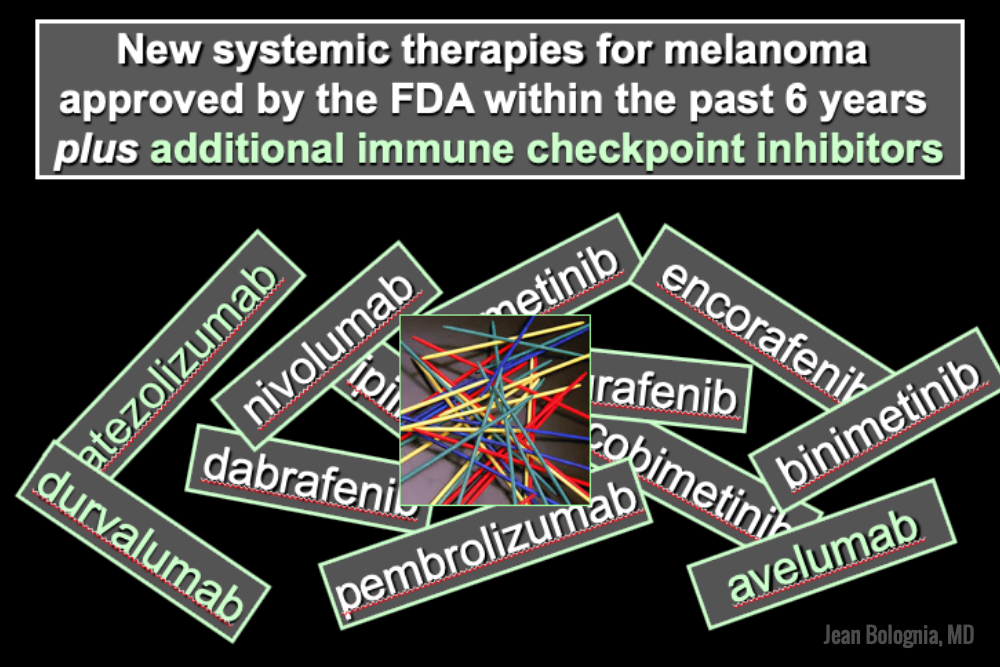

The world of melanoma is evolving, and dermatologists need to be equipped with the knowledge to help their patients navigate this landscape. Newer therapies for patients with more advanced stages of melanoma have not only drastically improved survival, but we as dermatologists must be prepared to recognize and treat the cutaneous side effects of these medications. This is a brief summary of common systemic therapies for melanoma with which every dermatologist should become familiar.

MAP Kinase Pathway Inhibitors

Selective BRAF Inhibitors

Melanoma tumor cells often have activating mutations that lead to constitutive activation of the MAP kinase pathway (See figure). Such activation can then lead to unregulated cell growth and proliferation. The most commonly detected mutation in BRAF results in the substitution of glutamic acid (E) for valine (V) at the 600th position in the BRAF protein and is referred to as BRAF V600E. Selective BRAF inhibitors, e.g. dabrafenib, encorafenib and vemurafenib, specifically target altered BRAF proteins. You can easily recognize these medications from their names, with raf indicating they target (B)RAF and nib identifying them as inhibitors. They are administered orally and chronically and lead to rapid responses but unfortunately tumor resistance commonly develops, often within six months. There are cutaneous side effects that the dermatologist should recognize, including morbilliform and folliculocentric eruptions, UVA photosensitivity (e.g. vemurafenib), keratoacanthomas/squamous cell carcinomas, and changes in melanocytic nevi (eruptive, enlargement, involution).

MEK Inhibitors

When mechanisms of resistance to selective BRAF inhibitors were investigated, a common finding was re-activation of the MAP kinase pathway via activation of MEK, another kinase that is downstream from BRAF. MEK inhibitors, e.g. binimetinib, cobimetinib, trametinib, were then combined with selective BRAF inhibitors to reduce the development of tumor resistance. These drugs are identified by the presence of a -metinib suffix. Interestingly, compared to BRAF inhibitors alone, combination BRAF+MEK therapy is associated with significantly less, not additive, cutaneous side effects – a real benefit to the patient.

Immunotherapy – Checkpoint Inhibitors

Immunotherapy is designed to stimulate the immune system to attack immunogenic melanoma cells. These monoclonal antibodies inhibit inhibitory signals that normally downregulate the immune system and thus act as immune checkpoints. These drugs model after the saying “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” only it’s now “the inhibitor of the immune inhibitor is the immune stimulator.” CTLA4 is a receptor on regulatory T cells that plays an important role in diminishing immune responses. By blocking the inhibitory function of CTLA4 during the priming phase, the anti-CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab increases T cell immune activity. Peripherally, when the PD-1 receptor on T cells binds to its ligand, PD-L1, on tumor cells, an inhibitory signal results. In a similar fashion, the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies approved for melanoma – nivolumab and pembrolizumab – can increase anti-tumor immune activity. Anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies (e.g. avelumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab) have been approved to treat other malignancies, including Merkel cell carcinoma.

Source: Next Steps in Derm

In a 20-minute lecture presented at the 16th Annual ODAC conference, Dr. Patel reviewed the appropriate management of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma. Grabbing the attention of the audience early on, Dr. Patel quoted the staggering statistics for squamous cell carcinoma – calling the growing epidemic “a public health crisis.” He challenged dermatologists to lead the charge in a more sophisticated approach to disease stratification.

Data are conflicting regarding the risk of progression of actinic keratoses to squamous cell carcinoma. Despite Dr. Patel’s expertise, he admitted even he finds it impossible to predict which lesions will progress. Instead, he takes a more astute approach and taking a step back to focus on the burden of disease.

With the groundwork firmly laid, Dr. Patel delved into the crux of his talk. He posed a thought-provoking question to captivated listeners: Are actinic keratoses a disease or a symptom? In the same way hypertension leads to stroke, actinic keratoses lead to squamous cell carcinoma.

Dr. Patel drove his point home with several instructive clinical cases. With each patient, Dr. Patel calls dermatologists to first discern field disease from invasive disease. Once invasive disease has been excluded, hyperkeratotic lesions should be debrided, and a strict regimen of topical 5-fluorouracil instituted for 4 weeks. This regimen should be followed by photodynamic therapy in 3 months.

Source: Dermatology News

When caring for individuals with sun-damaged skin, dermatologists need comfort with the full spectrum of photo-related skin disease. From assessment and treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs) and field cancerization, to long-term follow-up of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), appropriate treatment and staging can improve patient quality of life and reduce health care costs, Vishal Patel, MD, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. On the other hand, he added, “field disease can be a marker for invasive squamous cell carcinoma risk, and it requires field treatment.” Treatment that reduces field disease is primary prevention because it decreases the formation of invasive SCC, he noted.